As retailers supposedly take over product innovation, they need to take heed of customers’ expectations around brands and their own offerings.

By David Burton and Colmar Brunton.

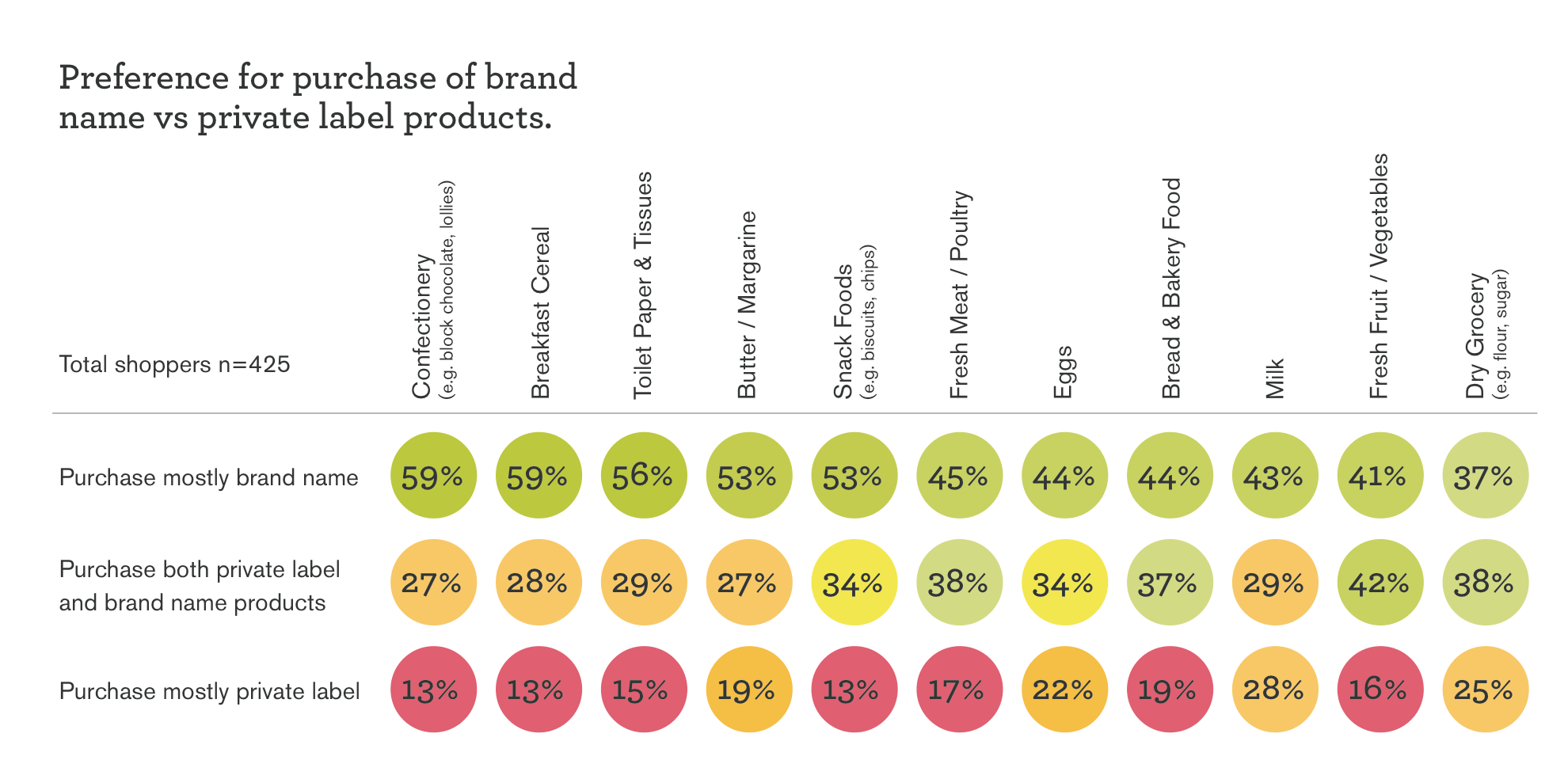

In this month’s Shopper Pulse, the panel was asked a series of questions regarding their use or dislike of private label products across a range of departments and categories. Because a similar survey was carried in our 2012 report, trends could be measured.

So what do consumers want from their shopping experience?

We all know of the value proposition for retailers’ own house brands. In many categories they offer a significant price discount against the market leader. In some categories the private label share is extremely high and in others it’s almost immeasurable.

However, numbers are one thing – with the Retail World Annual Report providing an absolute measurement of what shoppers have bought over a 12-month MAT period – while the Shopper Pulse looks at attitude and intent, and makes for interesting reading.

In the Australian market, private label is big business for retailers and those suppliers lucky enough to win the tenders.

In the US, the category of private brands, as the market calls them, is seeing slowing growth, especially compared with the private-brand industries in other countries. So says the Food Marketing Institute (FMI).

“What is needed is to move our private brands industry from transactional-based relationships to a more collaborative relationship,” the institute said at the FMI Private Brands Business Conference in late 2014.

To help achieve this, the FMI is teaming up with global consumer products and retail management consulting firm The Partnering Group to build a Collaborative Private Brands Business Planning tool. This is a retail and supplier business planning process aimed at helping accelerate and drive private brand development.

In Australia, private label is such a specialist segment that it even has its own industry association. The Private Label Manufacturers Association has supplier and retailer members and meets regularly to discuss issues and trends facing the segment.

The category split

When asked what categories from a list the respondents shop for, private label milk scored highest with 20 per cent of consumers continuing the trend towards saving money at the register. Milk is, in fact, cheaper than petrol, in spite of recent lower pump prices, at $1 per litre for Coles and Woolworths products.

Dry grocery came in second in terms of products most purchased by private label shoppers, with sugar and flour prominent in the nominated items.

Interestingly, when it comes to ordinary old flour, a kitchen staple, specialist brands and products with a specific purpose help keep brand share from falling further.

Eggs are another category where private label has a significant share. Retailers have pushed the profile of their own products as they move to cage-free and more organic ranging.

Conversely, in the cereal category, a high 40 per cent of shoppers always buy brands. This segment is ripe for erosion of brand share as more lookalike products under the retailers’ brands mimic the brand leader in various sub-categories.

For confirmed confectionery fanciers, a wide choice of brands is available and, again, retailers have mimicked popular lines in their ‘share packs’. Notable knock-offs include versions of Mini Mars Bars, Twix and Snickers. In spite of the selection available under retailers’ own brands, 37 per cent of shoppers buy only national brands.

Butter is butter, right? More than a third of consumers have a preference for a branded butter or margarine compared with a private label offer, with just 12 per cent always buying house brands.

What the shopping public wants

When it comes to brands, consumers want to see more branded breakfast cereal on-shelf versus private label. More than two-thirds of the panel have this preference.

In the market for toilet paper, almost two-thirds want brands. They’re spoilt for choice in the supermarkets, with many brands at everyday low prices while others are subject to regular hot discounts that show prices of 35¢ per roll or better.

Coles has had its Quilton 20-pack at the same, low, $10 shelf price for around three years. It was one of the early products offered in the ‘Down, down’ campaign and, although not a private label product, it has maintained the reduced price to offer private label value on branded quality.

More than half of consumers want branded bread, and the recent spate of competition over the 85¢ loaf between Woolworths, the leader on this, and Coles, which followed, is squarely aimed at a particular segment of the market. This loaf represents only a small proportion of the major branded lines, but it proves you can make bread to a price if you change the specifications.

With just under half of bread shoppers always buying private label, this is a wide market to succeed in.

Fresh meat and poultry provide an interesting segment, because more shoppers buy private label, by a small margin. In this segment, particularly in red meat, the range is mostly packed under the retailer’s name.

Poultry is the more brand-oriented, with the well-known offers from Steggles, Lilydale, Inghams and Luv-a-Duck all providing whole birds, portions and value-added lines that add variety to the meat cabinet and drive more choices for meal solutions. Innovation from the brands will often flow into the retailer’s own packaging.

Comments from consumers

When asked whether they regarded private label products as being just as good as those with brand names, some panel members provided some interesting notions. This response is sound advice for us all: “You need to try them. A lot of them are just as good as brands, but some are horrible.”

Another response put the spotlight on a major issue facing suppliers: “Yes, but choice is severely limited in some lines and departments now. Choice is good for all of us and the brand providers.” This respondent has identified the conundrum for suppliers – resist private label or fight for tenders when they arise.

Brand providers would argue that there is already too much choice in private label and so-called control brands.

More and more suppliers talk of “presenting” lines and being asked if they would be interested in supplying these under a retailer’s own label.

So which came first, the chicken or the egg? Can suppliers complain about retailers’ private label push if it’s consumer driven? Or is it consumer-driven only because sales growth in private label is a result of restricted brand choice?

One respondent said: “Private label are (sic) usually not as good quality. Private label are (sic) reducing the choices at the supermarket.” This seems to sum it up.

In a recent report on the state of Australia’s supermarket sector, Macquarie Research commented: “[The] shift to private label in Australia is being accelerated by ALDI. Woolworths and Coles’ private label product development is continuing to evolve. This ongoing evolution is necessitated by the increased relevance of discount supermarket ALDI, which appeals to customers in part through low-cost private label products.”

Macquarie Research also noted that the Australian market had some way to go before reaching the private label market shares of Europe. We do outscore the US and Canada on (per capita) private label spending, though.

Private label products win prizes

Any discussion on private label needs to mention ALDI and its own brands. With a restricted range of national brands available in its stores, ALDI relies on the wide range of its own brand names, exclusively developed by the business, which mimic brand labelling.

In fact, ALDI sees these products as being as good as the national brands and conducts comparative advertising of the prices of equivalent baskets. But it isn’t just about the price at ALDI: the products have won awards at the various state dairy industry shows and in other arenas.

In fact, from a private label perspective, Coles, Woolworths and ALDI recently took out a combined 16 awards at the 2015 Product of the Year Awards. These are examples of private label products, with national brand quality and innovation, working to save the consumer money at the register.

So, which is better, private label or national brand? This is a simple question without a simple answer.

The reality is that both are good options providing the quality is acceptable on the private label offer. Some things cannot be replicated. Toblerone is one that comes to mind. The unique flavour of Coke or Pepsi is mandatory for each of its fans. Others find a house brand cola refreshing, without the brand hoopla.

Marketers and sales directors are continually told to find a point of difference, not try to compete on price, and ‘innovate or perish!’ These days, the retailer is likely to want this innovation under its own brand.

And with long-range planning under collaborative account management, it can likely launch an idea ahead of the supplier that thinks it is delivering innovation.

Do the consumers care? Not a jot. They’re too busy balancing their own budgets as they inadvertently decide who wins and loses in the battle for supermarket space.