Paul Stringleman

Senior Consultant

Paul has developed several data- driven automated warehouse solutions for e-commerce and retail companies in Australasia, including Coles Retail Ready Meats – a fully automated warehouse that uses robots to pick crates of trayed chicken and red meat for 900 stores along the eastern seaboard.

He has developed several data-driven automated warehouse solutions for e-commerce and retail companies in Australia.

About Swisslog

Swisslog designs, develops and delivers best-in-class automation for forward-thinking health systems, warehouses and distribution centres. It offers integrated solutions from a single source – from consulting to design, implementation and lifetime customer service. Behind the company’s success are 2,500 employees worldwide, supporting customers in more than 50 countries. Swisslog is a member of the KUKA Group, a leading global supplier of intelligent automation solutions. www.swisslog.com

How incremental improvements can impede innovation in automation of retail warehousing and distribution.

Kaizen and kaikaku

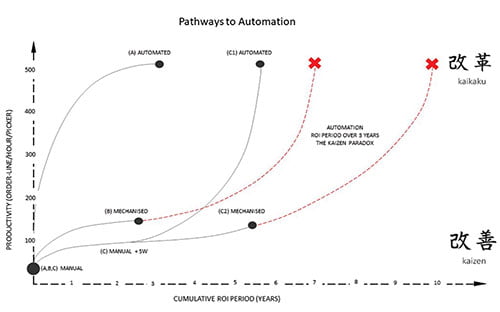

Kaizen is a Japanese word meaning ‘improvement’. In business, it is a concept that refers to small, continuous steps to a better process. Many globally renowned companies – such as Toyota in Japan – use kaizen practices to guide their management and strategic thinking, but there are times when kaizen is not enough. Worse still, a small improvement can often hold an organisation back, perhaps even stifling significant development.

This is the kaizen paradox. Another Japanese concept – less well known, but equally important to highlight – is kaikaku, or ‘radical change’. Kaikaku describes the other side of improvement: the major step forward, or big leap. An analogy to describe the kaizen paradox is a home illuminated by candles: while kaizen improves upon the candle, kaikaku is the installation of electric light.

Paradox in practice

In a recent real-world example, a company was seeking to identify a solution for an automated ‘goods- to-person’ warehouse in a bid to achieve a significantly higher level of business performance. However, the company had already invested in a mechanised ‘zone-to-zone order picking’ solution a year earlier.

Although this project was still in the commissioning phase, senior management could see that it wasn’t going to meet their longer- term requirements. Fortunately, the mechanised solution didn’t occupy the entire warehouse, making it possible to build an automated goods- to-person solution on the same site.

It soon became clear that the mechanised system made it much harder for them to proceed with the automation they required, as the business had invested a large sum on a now largely redundant piece of equipment that occupied a prime position in the warehouse. Unless the mechanised system could become part of the fully-automated solution, the company also faced the cost of scrapping the new installation.

While the mechanised system improved productivity from 50 to 150 order lines per hour per person, the automated goods-to-person system would deliver 500 order lines per hour per person. As a result, almost a third of the productivity gain that would have been realised in going from a manual to an automated operation was already delivered by the mechanised system. This worsened the business case, extending the ROI of the desired automated system by an extra year. Because the mechanised system could not be incorporated in the automated solution, there was no reduction in the cost of the required automation. This is the kaizen paradox at work.

Tools and approaches to support best practice

Both manual and mechanised warehouses involve ‘goods to person’ in some form. Mechanised improvements have helped reduce the time between pick operations and gradually lift productivity from around 50 to 150 order lines per hour per picker.

The kaikaku occurred when goods-to-person technology was developed that radically transformed the way orders were picked, allowing a stationary worker or a robot to pick from products delivered to them in sequence. This can typically boost individual picker performance to between 500 and 1,000 order lines per hour and minimise the labour required, while at the same time significantly reducing the warehouse footprint due to higher- density storage.

An automated goods-to-person warehouse can typically achieve the same throughput as a manual or mechanised operation, with around half the staff and in half the building size. As a result, a strategic approach to automation can save significantly on the cost of warehouse expansion or remove the need for relocation, prolonging the life of the existing facility.

This more strategic approach to kaikaku can protect an organisation from being trapped in a focus on low- performance operations and being cursed with the kaizen paradox.

Next steps for boards and managers

For successful organisations, major leaps forward in performance are often approached strategically. Kaikaku investments are made before kaizen improvement. Every business is striving to improve, but not all improvements are complementary or equal. Opportunities to stay ahead of the competition can be stalled by an organisation’s own efforts. Critical to enduring competitiveness are a regularly reviewed strategic approach to improvement and a long-term strategy to deliver.

The kaizen paradox is a common predicament for many businesses, where investments are made to achieve productivity gains, but in doing so they dilute the business case for a better investment, causing them to plateau at a lower level of productivity. Once organisations are aware of the potential for investments that create a kaizen paradox, they are better able to consider potential improvements as part of a bigger, longer-term picture.